Quarterly Economic Review 4th Quarter 2022

Looking back; Looking ahead

Will the road to recovery run through recession?

Unfortunately, U.S. equity markets did not end 2022 on a high note with their usual “Santa Claus rally.” Rather, the latter part of December and even the first trading days of 2023 were mostly disappointing and downward trending. Indeed, the major U.S. equity indices turned in decidedly negative performances during 2022 with the tech-heavy NASDAQ down over 32%; the S&P 500 down 19.44%; the S&P 400 down 14.48%; and the S&P 600 down 17.42%. The pain was felt throughout the equity markets as evidenced by ten of the eleven S&P 500 industry sectors ending the year well into negative territory. Only the energy sector turned in a positive performance for 2022 (+59.04%). The other ten sectors were down anywhere from 1.44% (Utilities) to 40.42% (Communication Services). As you are probably well aware, the U.S. bond market did not fare much better. The 30-year Treasury ended 2022 down 33.25% while the 10-year Treasury was down 16.69%.

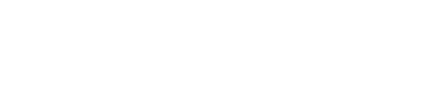

Domestic equity markets were not only decidedly negative this year — they were also fairly chaotic. This can be seen by the unusually high number of times in 2022 the major equity indexes moved 1% or more during a single trading day. As the chart to the left shows, you need to go all the way back to 2008, during the height of the financial crisis, to match the number of extreme down days the S&P 500 experienced in 2022. Prior to 2008 and over the past 80+ years, only the bursting of the dotcom bubble in 2002 and the combined inflation/recession/bear market in 1974 surpassed this year’s high volatility.

As we turn the calendar on a new year, economists and investors find themselves grappling with conflicting economic data and concerns about what might be in store for the U.S. economy and financial markets in 2023. At the heart of these concerns lies a fundamental question:

Will the Fed prove successful in its efforts to drive inflation back down around its target 2% rate without overstepping the mark and inadvertently pushing the U.S. economy into a recession?

Depending on the day of the week and the economic data of the moment, different pundits are offering up different answers to this question. According to a mid-December survey Bloomberg conducted with 38 economists, for example, there is now a 70% chance a recession will occur in 2023.1 But, a number of other economists do not agree. For example, Jan Hatzius, the Chief Economist for Goldman Sachs, recently opined that the U.S. will avoid a recession in 2023.2 Goldman Sachs is not alone in this belief. Mark Zandi, the Chief Economist for Moody’s Analytics, recently stated the U.S. will most likely experience a “slowcession” rather than a full-out recession in 2023. Moody’s defines a slowcession as a period of time where “economic growth ‘comes to a near standstill but never slips into reverse.'"3

There is already some indication the Fed’s numerous federal funds rate increases in 2022 may be starting to have the desired impact by slowing the U.S .inflation rate. For now, it appears the U.S. inflation rate peaked in June at 9.1% — the highest rate in over 40 years. The most recent Consumer Price Index data (11/22) shows the U.S. inflation rate is 7.1%. A meaningful drop in the price of oil since June and an improvement in the supply chain issues that resulted in numerous product shortages over the past few years have helped on this front.

But, inflationary concerns both in the U.S. and overseas persist and there is no clear consensus that inflation will continue to ease as the year progresses. If anything, inflation remains a bit of a wild card and rising wages are a key culprit. Even though wages in the U.S. have been on the rise for many months, workers are falling behind due to inflation. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that U.S. workers saw their wages and salaries rise by 5.1% for the 1-year period ending in September 2022.4 This increase — while robust — is significantly less than the rate of inflation. As a result, workers are demanding more in wages and often receiving what they ask for thanks to a shortage of available workers and a low unemployment rate (3.7%). Federal Reserve Chairman Powell recently pointed to rising wages and the labor shortage as key drivers of the much higher than desired inflation rate persistently sticking around in the U.S. economy.5

The Impact of Fed Rate Hikes

In terms of where we might be headed from a federal funds (“fed funds”) rate perspective, it helps to review where we have been over the last year. At the start of 2022, the fed funds rate was in a range of 0% – 0.25% and 6-month Treasuries were yielding around 0.21%. At year end, the fed funds rate range was 4.25% – 4.50% and the 6-month treasury yield approached 4.8%.

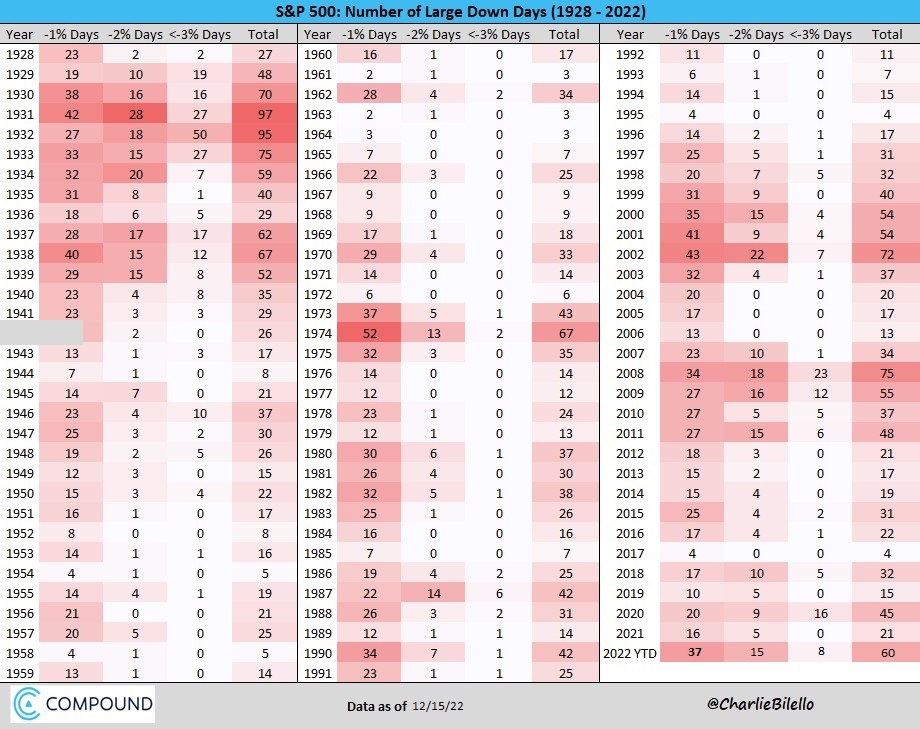

Along with a series of 75 basis point “bp” rate increases earlier in 2022 followed by a 50 bp increase last month, the Fed’s current hawkish monetary policy is also focused on removing money from the U.S. economy by reducing its own balance sheet. As you can see in the chart, the Fed’s balance sheet ballooned from less than $1 trillion in mid-2007 to nearly $9 trillion by April 2022. This massive expansion initially was driven by a desperate effort to stave off a potential financial-crisis-induced depression back in 2007– 2009. Once that crisis passed, the fed had a relatively small window of time within which to begin reducing its balance sheet before it again had to provide massive monetary support to the U.S. economy through the darkest days of the COVID pandemic.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve system

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve system

Unfortunately, the Fed is again only in the very early stages of reducing its balance sheet — there is still a long way to go, and this monetary tightening could continue to act as a headwind. As expected, the swift and decisive increases in the fed funds rate this year drove borrowing rates up meaningfully. For example, a year ago a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage sported rates around 3.3%. This month, that same mortgage is twice as expensive at around 6.5%.6

The rapid increase in interest rates also adversely impacted bond prices throughout 2022. It is extremely rare for stocks and bonds to both be down at the same time. Generally, these two assets classes are not highly correlated with each other. This is one reason why investors rely on bonds to offer a measure of protection when the stock market falls. But this year has been a marked exception. Bond prices are inversely related to bond yields. Thus, as bond yields rose throughout2022 (due to the Fed’s aggressive fed funds rate increases), bond prices fell.

Not surprisingly, given the negative performance of both stock and bond markets, 2022 has also proven to be one of the worst performance years on record for balanced portfolios. In fact, a 60/40 portfolio (60% stocks as represented by Vanguard’s Total Stock Market ETF/VTI and 40% bonds as represented by Vanguard’s Total Bond Market ETF/BND) fell by 16.5% this year.7

Looking Ahead to 2023

Although somewhat hamstrung by monetary tools that take a long time to work (generally it takes about 6-9 months for a rate increase to filter its way through the U.S. economy so its impact can be gauged), the Fed has hinted its future rate increases will likely moderate further. It is possible the Fed will impose just a couple more 25 bp increases early on in 2023 as it attempts to fine-tune monetary policy.

However, any hopes for a near-term pivot towards lower rates seems wildly optimistic. As noted above, the Fed is still keenly focused on a strong U.S. labor market where unemployment remains historically low, there are way more open jobs than available workers, and wages continue to steadily rise; all of which could serve to keep inflation unacceptably high. Additionally, Congress just passed, and President Biden signed, a $1.7 trillion spending bill to avert a government shutdown. This ‘loose’ fiscal policy may exert added inflationary pressure.

Given this, we believe a much more likely scenario is a couple more smaller rate hikes in 2023 followed by an extended hold period that may last into 2024, before possible rate reductions would be used to once again stimulate economic activity. The probable result? Continued moderating inflation along with a potentially mild recession here in the U.S. coupled with a deeper recession in Europe.

Even given the current challenging economic environment, several tailwinds exist:

- China (where lengthy and extensive lockdowns caused economic growth to come to a virtual standstill) has finally begun easing its COVID restrictions and has set a 5% GDP growth target for the coming year.

- With Democrats losing control of the House, we will once again have a bipartisan government. History shows that U.S. financial markets tend to perform better when government is

divided rather than just one party in control. - Economists generally consider a U.S. unemployment rate of 4% – 4.5% to constitute “full ” Given that our unemployment rate is 3.7%, our economy appears poised to handle a modest rise in the unemployment rate without significant adverse economic consequences. If anything, a tick up in unemployment has the potential to reduce some of the wage pressure currently fueling inflation.

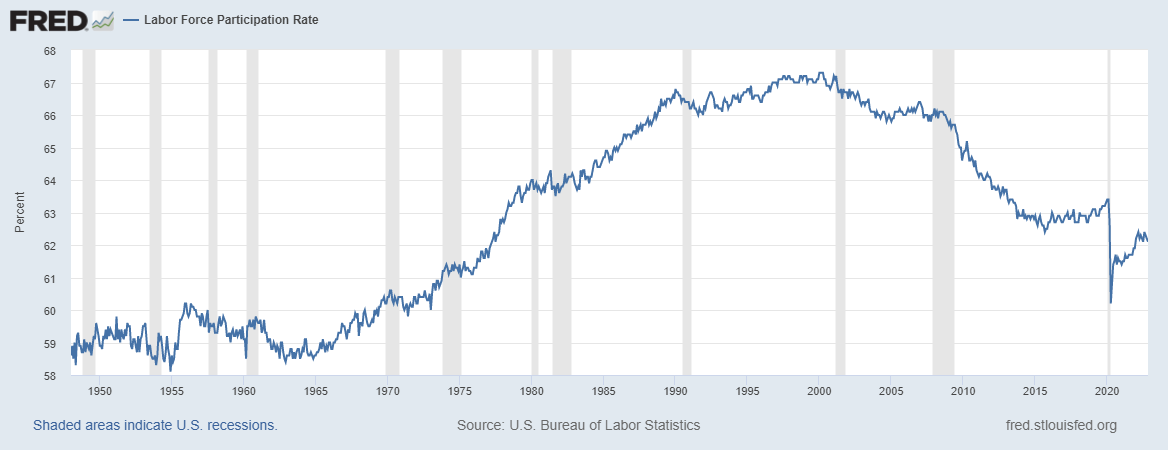

Going forward, we will also continue to closely watch the U.S. labor force participation rate —the number of people in the labor force as a percentage of the civilian non-institutional population. For the past 20 years, this rate has been steadily declining (from 66.4% in 2002 to 62.1% today). Although somewhat recovered from its 2020 pandemic-induced low, the rate is still below where it stood in early 2020 and well off its 66-67% range between 1989 and 2007. As the chart below depicts, we are now back to levels not seen since the late 1970s — a time when large numbers of women were only just beginning to enter and remain in the workforce. Demographically, we are in the midst of a global worker shortage and talent gap that may become an issue of growing significance in the future.

We are also monitoring the effects, both here and abroad, of other central bank activities. Japan recently and unexpectedly loosened its monetary policy while other central banks across the globe (e.g. the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Swiss National Bank) are tightening their monetary policies.

2022 proved to be a difficult year for nearly every securities market and every economy around the globe. Looking to the year ahead, however, we see much to be positive about as the U.S. economic ship is slowly righted, patched, and set to sea. In the meantime, and as always, your BLBB advisor is available to answer any questions you may have and/or help you explore ways to better recession-proof your portfolio (215-643-9100).

1 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-12-20/economists-place-70-chance-forus-recession-in-2023?srnd=premium&leadSource=uverify%20wall

2 https://seekingalpha.com/news/3919582-no-recession-norate-cuts-in-2023---goldmansachs-chief-economist

3 https://www.cnn.com/2023/01/03/economy/moodys-us-economy-slowcession/index.html

4 https://www.bls.gov/news.release/eci.nr0.htm

5 https://apnews.com/article/inflation-business-pandemics-jerome-powell-federal-reserve-system-01ca0f8ac5439f764827fb-89d18a51e7

6 https://www.cnbc.com/2023/01/04/mortgage-demand-plunges-interest-rates-rise.html

7 https://portfolioslab.com/portfolio/stocks-bonds-60-40