Quarterly Economic Review 3rd Quarter 2022

Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Inflation, Recession, and The Fed’s Role

Despite a significant reduction in U.S. energy prices since our last update, recent economic data indicates more persistent, widespread, and stubbornly high inflation in the U.S. economy than originally anticipated. Accordingly, and as expected, the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (‘FOMC’) approved a third consecutive 75 basis point (+0.75%) rate increase at its September meeting. This was the fifth consecutive fed funds rate increase since March 2022 and this key interest rate now hovers in the 3% - 3.25% range. The last time the fed funds rate was this high was in early 2008; and as you can see in this chart, it’s been a long time since we experienced anything even closely resembling this accelerated pace of rate increases.

In addition to raising the fed funds rate in late September, FOMC members also reiterated their longstanding goal of targeting a 2% inflation rate and provided insights into how the U.S. economy might perform over the coming 24 months and what this could mean for future fed funds rate decisions. In particular, FOMC members noted investors should expect:1

- The fed funds rate to reach around 4.25% – 4.5% before year-end and then peak at 4.5% – 4.75% during the first half of 2023;

- The U.S. unemployment rate (currently at 3.7%) to climb to around 4.4% next year;

- Inflation to gradually recede but remain above the 2% target rate through 2023 and 2024;

- The fed funds rate to remain above its target range (i.e., 2% - 3%) potentially into 2025 or longer; and

- US GDP to possibly stumble in 2023, with downside risks outweighing upside potential.

Not surprisingly, other central banks have also embarked on their own rate increases in an effort to curb inflation—including the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Reserve Bank of India, Brazil’s Central Bank, Bank of Canada, and Banco de Mexico.

A closer look at inflation

For months, several economists, government officials, and pundits espoused a narrative suggesting that rising energy prices were primarily to blame for soaring inflation in the U.S. Many also placed the blame for rising energy prices on Russia’s war in Ukraine and the lingering effects of COVID on the global supply chain. The general presumption was that once energy prices began to abate, inflation would quickly follow suit.

Unfortunately, this has not been the case—at least not yet. Since early June, for example, retail gasoline prices in the U.S. fell from $5.03 to $3.81 per gallon. Despite this 24.25% reduction in the price of gasoline at the pump, current inflation data (CPI, PPI, and PCE) remains stubbornly robust and suggests several other factors beyond energy prices are contributing to inflationary pressures in the U.S. The August Consumer Price Index print (released in mid-September) showed significant increases in food, shelter, and medical expenses. Also, year-over-year, the ‘food at home’ index has risen 13.5%—the largest 12-month increase since March 1979.2

The latest Personal Consumption Expenditures price index (PCE) data, released on 9/29/22, revealed a higher than expected 7.3% year-over-year price gain during the 2nd quarter of this year and was just shy of the 7.5% gain reported for the 1st quarter of 2022.3

Recent jobs data issued by the U.S. Department of Labor was also surprisingly strong—showing jobless claims by U.S. workers were well below estimates and had fallen to their lowest levels in over 5 months.

In other words, some of the latest economic data suggests inflation could be a bit more entrenched in the U.S. economy than originally thought and may result in additional aggressive policy moves by the Fed. Further compounding this situation are recent government policies (e.g., approval of the student loan forgiveness program and passage of the Inflation Reduction Act) which promise to pump even more money into an already overheated U.S. economy. These policies directly conflict with the Fed’s ongoing efforts to control inflation by passively removing some of the trillions in quantitative easing it injected into the U.S. economy during the pandemic. Also, we would be remiss if we did not mention that energy prices have the potential to retest recent highs as we move deeper into peak heating season—especially if Russia enforces its numerous threats to cut off oil and natural gas exports to Europe and the rest of the world.

Implications of a soaring U.S. dollar

During periods of great turmoil and economic uncertainty, there is often a flight to the U.S. dollar which tends to be viewed as the world’s safe-haven currency. As a result, and as clearly depicted in the U.S. Dollar Index (DX) chart below, over the past 18 months our currency has soared relative to other world currencies. The dollar, which for 20 years has been priced lower than the Euro, is now worth more (1 USD = 1.04 Euros). And the traditionally large gap between the value of the British pound sterling and the U.S. dollar has dramatically narrowed (1 USD = .94 GBP).

The strength of the U.S. dollar can also be attributed to other factors—including that the U.S. economy, of late, has consistently outperformed most other developed economies across Europe and Asia. European economic growth has been hampered by both the Russia/Ukraine war and the resulting energy crisis, while many Asian economies have been tangentially harmed by China’s extreme COVID policies.

Although a strong dollar is advantageous when you are traveling overseas, it tends to act as an economic headwind in several ways:

- Large U.S.-based multinationals could take a major financial hit when their overseas sales conducted in foreign currencies need to be converted back into U.S. dollars (U.S. corporate earnings have yet to reflect this possibility);

- Countries with large debts mostly denominated in U.S. dollars may find it increasingly difficult to keep up with debt payments because the values of their own currencies have eroded against the dollar (e.g., Turkey and Argentina); and

- Companies outside the U.S. are finding it harder to pay for raw materials and components they need to run their businesses, as many of these are denominated in U.S. dollars.

Recently, we saw both the Bank of Japan, and China’s Central Bank step into the currency market (increasing purchases of their own currencies and selling dollars) in a bid to stop the rapid fall of their currencies’ values. In Japan’s case, interventions are very rare, highlighting just how troublesome a too-strong dollar can be for other economies. We also just saw the Bank of England announce it will start buying “gilts” (UK government bonds) in an attempt to stabilize its turbulent fixed-income markets.

Does all this mean a recession is more likely?

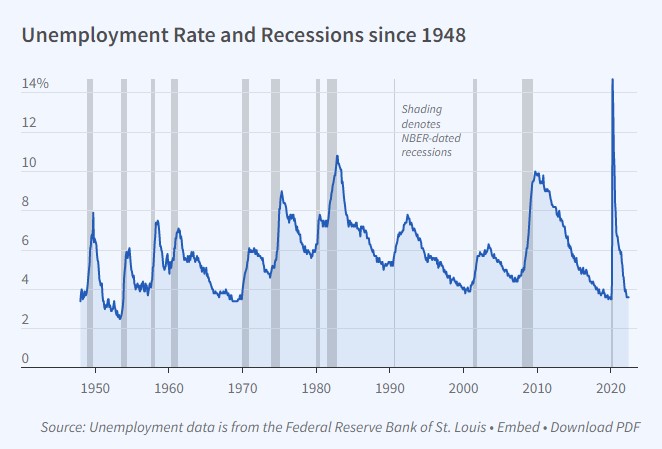

Despite two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth (-1.6% in Q1 and -0.6 in Q2), the National Bureau of Economic Research (‘NBER’) has yet to declare an official recession. The chief mitigating factor? An extremely low (3.7%) current unemployment rate combined with a plethora of available jobs. As the following chart shows, nearly every U.S. recession has been accompanied by a spike in unemployment.

Even though we have yet to see any real upward movement in unemployment, some economists believe the U.S. economy is already in recession, or teetering on the brink, and that this will eventually be confirmed by the NBER later this year or in early 2023. We expect that eventually, the cumulative effect of the ongoing concerted effort by many central banks to fight inflation will likely bring about a recession in multiple countries. In fact, some recent economic data is already beginning to flash early warning signals:

- The U.S. Leading Economic Indicators Index has been on a downward trend for the past 6 months, suggesting the risks of the U.S. economy entering a near- to mid-term recession are heightened. (see the below chart);4

- The bond market’s inverted yield curve (with the 2-year Treasury yield outpacing the 10-year yield) is often another telltale recessionary signal;

- Deutsche Bank is now predicting a harsher than originally expected European recession—mostly due to the energy crisis now gripping the continent;5

- Thanks to major increases in food and energy prices, European inflation is now at 10%—the highest rate recorded there since the euro was created over 20 years ago;6 and

- And China’s economy also appears to be weakening. GDP growth rose by just 0.4% over the last four quarters—a far cry from the target growth rate of 5.5%.

The real-world impact of rising rates

How will a rising fed funds rate affect your everyday life? Expect a slowdown in home sales (and therefore a drop in housing prices) as mortgage rates steadily climb. The average 30-year fixed rate mortgage in the U.S. now stands at 6.43% (compared to just 2.96% earlier last year).7 Similarly, substantially higher credit card and car loan rates should start to hamper major purchases and overall consumer activity. Keep in mind, the U.S. consumer is responsible for about 70% of U.S. economic activity. A financially strapped consumer tends to consume less, which should eventually result in a slowing of U.S. economic activity.

The real unknown, however, is whether or not the Fed will be able to navigate the U.S. economy through a measured and controlled economic slowdown that brings inflation back to the desired 2% level but does not also result in a recession somewhere along the way. This is an exceptionally difficult task and history suggests the Fed may err on the side of being too aggressive, or persistent, in its efforts to control inflation, thereby inadvertently throwing the U.S. economy into a shallow recession. Only time will tell how it all plays out from here.

In general, more and more people are feeling squeezed by significantly higher costs for food, shelter, medical care, and other essential goods and services—not to mention higher interest rates for future loans they may need.

There are several economic and geopolitical uncertainties at the moment—from the upcoming U.S. mid-term elections to ongoing China-Taiwan tensions, growing concerns over the stability of Putin’s regime in Russia, nuclear threats, growing social unrest in Iran, and an escalating food insecurity crisis taking hold around the globe.

At BLBB, we expect this uncertainty to drive ongoing market volatility in the short term. Hopefully, as we begin to gain clarity on some of these issues (e.g., mid-term election results a month away), we should begin to see volatility recede.

In the meantime, we will be keeping an especially close eye on both the unemployment rate and U.S. corporate earnings (as well as forward guidance) to gauge how strong of an economic headwind rising rates will ultimately turn out to be. We recognize this is a turbulent time and market volatility can cause investors stress and concern. As always, however, your BLBB advisor is available to answer any questions you may have and to provide any other financial guidance you may need. Do not hesitate to give us a call (215-643-9100) or send an email!

Also, if you should find yourself with additional “cash on the sidelines” in a money market or savings account, consider investing at least some of this money in short-term U.S. government bonds (“Treasuries”). As of 9/30/22, a 3-month Treasury yielded 3.3%, a 6-month yielded 3.9%, and a 1-year yielded 4%. In most cases, these yields exceed what you can earn in other relatively low-risk investments like CDs, money markets, and savings accounts.

1 FOMC Summary of Economic Projections, September 2022

2 “Inflation isn’t just about fuel costs anymore,” CNBC, September 13, 2022

3 https://www.cnbc.com/2022/09/29/jobless-claimshit-five-month-low-despite-fedsefforts-to-slow-labor-market.html

4 U.S. Leading Indicators, The Conference Board, September 22, 2022

5 “Deutsche Bank says it now expects a ‘longer and deeper’ recession in Europe as the energy crisis takes a turn for the worse,” Fortune, September 21, 2022

6 https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/30/business/eurozone-inflation.html

7 Bankrate Weekly Mortgage Rates, September 27, 2022