Higher for Longer

As U.S. and global financial markets contend with upcoming economic data and what it reveals about the state of the markets, we expect to see continued volatility. A number of geopolitical issues may further inject financial uncertainty. Still, we believe it is prudent to remain invested in a well-diversified portfolio that matches your particular risk tolerance. Your BLBB Advisor is here to guide you.

2023 began in much the same way as 2022 ended; with all eyes carefully watching inflation data and the Federal Reserve. Taming runaway inflation has proven to be a difficult challenge for Chairman Powell and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

As the chart below demonstrates, the rate increases are beginning to have the desired effect. Inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), continues to gradually ease after peaking last summer. Still, it remains quite elevated — more than 2.5x the Fed’s target 2% annual rate — and now stands at 6%; down from January’s 6.4% reading. But core CPI (removing more volatile food and energy prices) only dropped by 0.1% from January’s 5.6% reading to 5.5%. Furthermore, Powell’s latest testimony suggests the Fed anticipates inflation may remain stubbornly elevated for longer than originally expected.

At times, fighting inflation with monetary policy conjures up images of the two-headed ‘pushmi-pullyu’ from Dr. Doolittle fame. Tighten the money supply and raise rates in an effort to slow economic growth and mute

inflationary pressures. But, then higher rates unexpectedly lead to unintended consequences (e.g., bank failures), which then could require a reversal and loosening of monetary policy to manage.

Too far — too fast?

As noted above, many of the Fed’s more recent rate increases have yet to fully impact the U.S. economy — causing some to worry that overzealous hiking might inadvertently tip the U.S. into a recession. Some economic indicators are certainly suggesting a recession may be on the horizon:

• Conference Board Leading Economic Index (LEI) — a gauge of expected economic activity about 6 months into the future — has fallen 3.6% over the six-month period between August 2022 and February 2023. This is a possible foreshadowing of recessionary pressures coming later in the year.

• Unemployment just ticked up to 3.6%; slightly higher than its recent 50+ year historic low of 3.4%. For now, unemployment remains at an exceptionally low level and there are still far more jobs open and available than workers to fill them. But, a number of companies (mostly in the tech sector) have begun announcing layoffs including Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon, Disney, News Corp., Zoom, BNY Mellon, FedEx, and Bed Bath & Beyond.

• U.S. credit card debt has also soared (up 18.5% in 2022) and continues to rise. Inflation is certainly a major cause of this — as consumers run up their credit card debt to pay for rising essential expenses such as food and shelter when wages fail to keep pace. It does not help that interest rates on credit card debt are now hovering around 21%!

Bank liquidity: crisis or hiccup?

Despite a loosening of bank regulations under the previous administration, bank balance sheets are far more solid now than they were leading up to the Financial Crisis in 2007 – 2009. Still, this did not stop the recent failures of SVB and Signature Bank (the 2nd and 3rd biggest bank failures in U.S. history) from sending shockwaves through the market as investors weighed concerns over possible further trouble amongst regional banks.

This was quickly followed up by Credit Suisse’s disclosure of material weakness announcement that it planned to borrow up to 50 billion Swiss francs (CHF) from the Swiss National Bank to bolster its liquidity, and then merger into UBS.

This confluence of news stories spawned a quasi-run on the banks — especially among individuals with balances in excess of the FDIC $250,000 coverage limit — moving their money into money market funds and treasuries. In addition, we’ve witnessed:

• A wholesale flight to quality by investors

• Gold prices on the rise

• U.S. treasury yields falling (the biggest decline since the 1987 stock market crash)

There is little question that rising interest rates are, in part, responsible for this weakness. As interest rates rise, bond yields follow suit and bond prices fall. Falling bond prices drive down the value of bank portfolios. However, in the case of SVB and Signature, a strong argument can be made that their liquidity crunches were the result of the former’s unique clientele (Silicon Valley start-ups) and the latter’s significant cryptocurrency deposits.

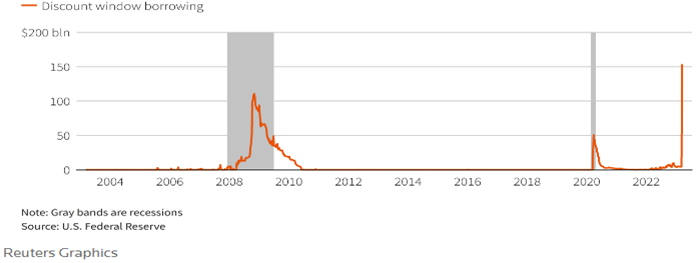

Whether this all proves to be a bump in the road or a canary in the coal mine (i.e., a one-off or a systemic problem) remains to be seen. At the time of writing this update, the Fed decided to open its emergency lending taps — allowing U.S. banks to borrow more than $150 billion during the few weeks — blowing past the previous record of $112 billion set during the Financial Crisis (see chart below).

In the meantime, regional bank stocks like First Republic (FRC -90% YTD) have been pummeled. And if the banking sector remains under stress, we may even see the imposition of tighter lending standards which, in

turn, could further contribute to slower economic growth.

The debt ceiling dilemma

Although somewhat hamstrung by monetary tools that take a long time to work (generally it takes about 6 – 9 months for a rate increase to filter its way through the U.S. economy so its impact can be gauged), the Fed has hinted its future rate increases will likely moderate further. It is possible the Fed will impose just a couple more 25 bp increases early on in 2023 as it attempts to fine-tune monetary policy.

Another lurking issue on investors’ minds involves the U.S. debt ceiling. The U.S. debt ceiling is “the total amount of money that the United States government is authorized to borrow to meet its existing obligations, including Social Security and Medicare benefits, military salaries, interest on the national debt, tax refunds, and other payments.”2 Currently, the ceiling stands at $31.381 trillion (a limit we reached in mid-January). However, thanks to some emergency maneuvering at the U.S. Treasury, a little breathing room was added but this will likely run out by early June at the latest.

This is by no means the first time we have reached the debt ceiling limit — and it almost certainly will not be the last. Since 1960, the debt ceiling has been raised 78 times! Each time, Congress simply voted for an increase and the problem temporarily resolved itself until spending reached the new limit. Given the heightened polarization and political animosity of the current Congress, we expect discussions around what the new limit should be, and when it will be implemented, will prove to be long, contentious, and generally painful. Already, various representatives are posturing, positioning, and holding out the possibility of blocking any debt ceiling increase (and in effect shutting down the government).

Failure to reach agreement before the deadline would prove extremely detrimental to the U.S. economy and the country as a whole. It is hard to conceive of a scenario where Congress would allow this to occur. But in this highly partisan environment, anything is possible.

Where do we go from here?

We all know how markets feel about uncertainty. Yet inflation remains a tremendous unknown. We have no idea when the Fed will put the brakes on current rate hikes, nor how soon they will decide to reverse course. Will the regional bank crisis spread? What will happen with the debt ceiling? What will the lead-up to the next presidential election cycle bring? And, what about the many ongoing global concerns — from the war in Ukraine to heightened tensions between the nations of the west and Russia, China, and North Korea.

The financial impact of the COVID pandemic continues to linger — particularly given the magnitude of the effort to stave off a massive worldwide recession or depression. It should come as no surprise that we are now encountering challenges as we ‘clean up’ after the unprecedented amount of fiscal and monetary stimulus injected into economies around the world.

Our markets have faced these kinds of issue many times before. When volatility peaks it can be extremely difficult to weather the storm. But throughout history, those moments have eventually passed, and even though there are no guarantees, the financial markets have historically recovered. Your BLBB Advisor (215-643-9100) is available to answer any questions.

1https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/monetarypolicy-what-are-its-goals-howdoes-it-work.htm

2U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2023

©2025 BLB&B Advisors, LLC. - PRIVACY POLICY – SITE USE POLICY – DISCLAIMER – ADV Part 2A – FORM CRS